Yi Yi: A One and a Two (2000, Edward Yang)

Normally I have a rotating group of favorites that I ritualistically watch every December, but this year, I’ve found myself returning to older comforts. A couple of nights ago, I rewatched Edward Yang’s Yi Yi, the Taiwanese director’s landmark final film from 2000. Quietly observing each member of the Jian family reckoning with the uncertainty of life in the aftermath of the family matriarch falling into a coma, Yang’s quotidian epic is a loving, sorrowful goodbye to a family member and a city, both of which act as omniscient, generous listeners for our characters to pour their lives into.

Yang’s film finds poignancy in a dual consciousness that runs through the film, one that’s intimately tied to each character’s inner turmoil, and another that speaks to omniscient wisdom deriving from the subconscious love of the grandmother and the gentle caress of the city. Aside from Yang’s typically top-notch master shots, framing each scene with swaths of narrative information of varying relevance, Yang’s collapse of the city symphony and family drama is predicated on an equal formal emphasis between character drama and a larger urban contextualization.

Among the most notable of these emphases is Yang’s singular use of reflective surfaces, shooting sequences through mirrors, doors, and windows, oftentimes foregrounding the urban landscape over character drama. This was a technique Yang explored previously, perhaps most famously in this sequence in A Brighter Summer Day, but is used to a much grander, systemic effect in Yi Yi. Yang similarly uses surveillance in an abnormal way, shooting his characters through CCTV cameras, or through overhead long shots, watching them from afar. While this sort of formal urban treatment is typically associated with narrative alienation, in works ranging from La Notte to Margaret, Yang’s use of the city is unique in its ultimate identification with its characters, breathing in tandem with the Jian family’s reckoning of the larger rhythms of life and death.

Min-Min, who realizes the repetitive irrelevance through talking with the comatose grandmother, decides to quit her job, leave her family, and attend a spiritual retreat. Min-Min’s decision to leave Taipei is subsumed into the hypnotic streets of the cityscape outside, gently echoing Min-Min’s wider anxieties regarding the meaning of her life. Min-Min finds no salvation in religion, which provides her no sense of purpose and reveals itself to be a scam. Meanwhile, NJ, Min-Min’s husband, begins a budding friendship with a Japanese video game creator named Ota, with whom his company wants to sign a business deal, and reconnects with his first love, Sherry, on a trip to Tokyo. NJ’s trip from Taipei to Tokyo is poetically expressed through a heartwrenching, ambiguous city reverie, which scrambles Taipei and Tokyo and the past and present, the omniscient city echoing NJ’s decades-long regrets, and the cold reality of how times have changed.

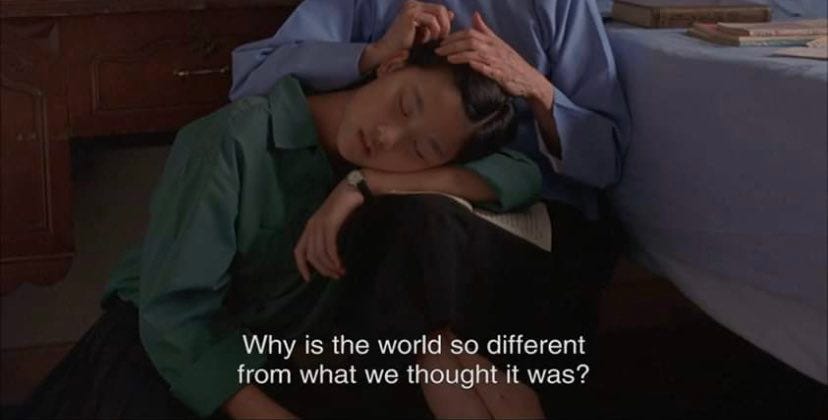

NJ’s time with Sherry is intercut with scenes of his daughter Ting-Ting’s first date with a boy named Fatso. Ting-Ting’s story is superficially reminiscent of Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, as she initially acts as a mediator between Fatso and his on-and-off relationship with Ting-Ting’s neighbor Lili. As Lili begins to see other boys, Fatso turns his eyes to Ting-Ting. NJ and Ting-Ting’s mirrored sequences, oftentimes with NJ and Sherry’s recollections of the past overlayed onto corresponding sequences between Ting-Ting and Fatso, form the most moving portion of Yi Yi. Largely shot through surveillance-style long shots, this section of the film is a lyrical sigh of generational change, gently questioning the possibility of human connection in the 21st century. NJ and Sherry’s reminiscing only reminds them of the impossibility of their relationship. They’re in a foreign country, Japan, no less, the country which formerly colonized Taiwan, and the pretense for their meeting, NJ’s career, is revealed to have been a core reason for their initial estrangement. The Taipei which fostered their initial love only exists in their minds, or perhaps in the reflections of the city that obscures their faces as they ride the subway. When Sherry disappears without a trace, and NJ’s newfound friendship with Ota is cut short by his partners making a business deal with some morally questionable knock-offs of Ota’s video game, two chances for human connection are cruelly taken from NJ. For Ting-Ting and Fatso, the rapidly changing modern landscape of Taipei is instrumental in her loss of innocence. Fatso was clearly never truly interested in Ting-Ting. Like the Bresson film, the possibility of romance is fading in the dying city. The ultimate conclusion of Ting-Ting’s romanticism is a cruel joke, and the specter of violence is always right around the corner. In a late dream sequence, Ting-Ting hallucinates being cared for by her grandmother. “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” she whispers. The ultimate perspective of Yi Yi, literalized through the grandmother’s headless embrace, is a knowing, compassionate caress.

The heart of Yi Yi lies with the Jian family’s youngest member, Yang-Yang. A troublemaker at school, Yang-Yang spends the film being teased by the girls in his class, getting reprimanded by a teacher for his playful nature, and discovering the prismatic nature of filmmaking. After being given an old film camera at the beginning of the film, Yang-Yang’s first forays in photography involve documenting his surroundings, hoping to prove the existence of mysterious mosquitos to his skeptical mother. Almost overly precocious, Yang-Yang asks if we can only ever know half the truth during an early car ride with his father. Later, he begins to photograph the back of people’s heads, often bowed down in achingly melancholy positions, showing his subjects what they can’t see. While disregarded by his teachers, who scoff at filmmaking’s lack of economic potential, Yang-Yang’s photographs are a testament to the power of filmmaking and the power of Yi Yi specifically. Filmmaking is Yang-Yang’s form of, if not revealing the unknown, altering his and his family’s relationship to their surroundings. It’s also a reminder of the existence of greater compassion, that the family is being cared for. In Yi Yi, the gaze of the camera, photographing its subjects from behind, is an ultimate act of familial empathy, an empathy that’s slipping away into the ether.

Yi Yi’s concluding funeral grieves for at least three deaths: the grandma, an old Taipei, and also Edward Yang, for whom Yi Yi was his final film, as he became diagnosed with cancer shortly after the film’s premiere, ultimately passing away before the end of the decade. The benevolent spirits of ancestors, the city, and the camera are all absent in Yi Yi’s heartrending final shot of Min-Min, NJ, and Ting-Ting tearfully watching the back of Yang-Yang’s head as he recites a speech he wrote for his dead grandmother, blissfully unaware of the world he’s entering into. The three deaths constitute something as apocalyptic as the death of humanity. It’s a tragic loss of collective compassion. The family’s replacement of these larger, omniscient forces expresses existential grief, an overwhelming mixture of love and fear as they face their futures in the city tragically alone.