The Beast (Bertrand Bonello, 2023)

Note: This is expanded from my previous writing on The Beast from here

When I saw Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast for the first time back in October, I was sure that I had witnessed not just the film of the year, but one of the great films of my lifetime. Having sat with it, and seen it two more times, my opinion of it has only grown. In a sense, The Beast is the ultimate Bonello film, integrating his ideas over the past decade (and revisiting the general time periods of House of Pleasures and Nocturama in the process) into a genuinely beguiling cinematic whats-it about humanity biologically losing its capacity for vulnerability.

Although Bonello has never enjoyed the wider recognition of contemporaries like Claire Denis or Olivier Assayas, he’s among my favorite directors. He’s a rare filmmaker whose work seems to defy articulation, and an artist whose films seem to spill out of his subconscious. His work is deeply concerned with how historical and sociopolitical changes affect our capacity to engage with the world, whether it be creating relationships or discovering ourselves, mutating these concerns into something scarily biological. A composer and director, Bonello is singularly adept at evoking the textures, surfaces, and atmospheres of what it means to live in a specific time and place in daring, unintuitive fashion. He often does this through a sensuous style, weaving together aesthetic inspirations of genre fare and arthouse cinema into something altogether more slippery and uncanny.

Perhaps the most exemplary work is 2011’s House of Pleasures. The film takes the core of its premise from Hou Hsiao Hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai. Set in Belle Epoque Paris at the dawn of industrialization, it follows a group of young sex workers at a struggling upper-class bordello. A sumptuous film that seems to take place in a gauzy dream state, the focus of the film is the girls’ sisterhood in the face of systemic exploitation, a sisterhood that movingly transcends profitability and beauty. While most of the film lies squarely in the early 20th century, there are consistent hints that the temporality of the film is unstable. This is most poignantly provoked during a wake on the eve of the bordello’s closure. Mourning one of their sisters and unsure of their futures in this emerging socioeconomic landscape, the girls engage in an unbearably melancholy slow dance to The Moody Blues’ Nights in White Satin, which Bonello pointedly marks as entirely diegetic. These anachronisms coalesce at the film’s conclusion, shot in grainy 2000s-era digital video, which suggests a modern version of this film with different social codes and concerns that’s lost the warmth of these girls’ deep social bonds. Profoundly, this warmth is also associated with the film’s extravagant surfaces, changes in society and humanity manifesting in film style and aesthetics, how the film shifts and complicates its surface textures. These ruptures speak to a racing anxious mind, a sense of despair, and a layering of historical experiences constantly in conversation, yet never quite aware of each other.

Since House of Pleasures, Bonello has taken an interest in the contemporary. Often focused on child subjects, the anxiety underlying many of these films is Bonello’s experience as a father imagining what the world will look like for his daughter. Nocturama, which is explicitly dedicated to her, centers a group of child terrorists who silently complete a coordinated attack on the city before hiding in a shopping mall for a Dawn of the Dead consumerist reverie. The film juxtaposes a propulsive first half composed of perpetual tracking shots with a second half submerged in dread-laden stasis as the children await their fate. The result is a self-conscious distress, and a fatalist sense of being existentially untethered. Following Nocturama, Bonello directed the Haitian-set Zombi Child, a story of colonial ghosts, set in a boarding school. In 2022, Bonello premiered Coma, a genre-bending personal piece which surreally envisions his daughter’s experience of the pandemic.

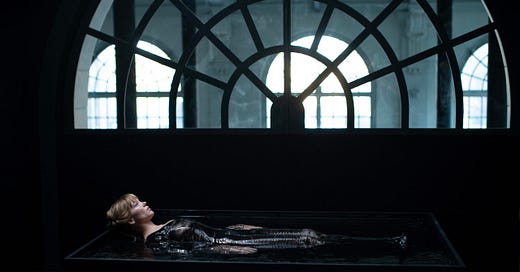

With The Beast, Bonello explores the contemporary by juxtaposing three different time periods. Like House of Pleasures, the substance of the film lies in how Bonello cuts between temporalities, tracing how history and aesthetics are constantly in conversation with each other, and how different sets of social codes uncannily reverberate. The overarching sci-fi premise of the film envisions the future of 2044, so quantified and sterile (shades of tech minimalism and the pandemic), that humans undergo a procedure to strip themselves of their past lives, a process which dulls their emotions, qualifying them for various forms of work. Loosely adapted from Henry James’ The Beast in the Jungle, Lea Seydoux plays Gabrielle, who doesn’t want to lose what’s left of her humanity, but reluctantly undergoes the procedure, delving into her past lives dominated by a series of missed connections with a man named Louis. In the Paris of 1910, Gabrielle plays a pianist who struggles to leave her husband for Louis. In a 2014 Lynchian L.A. (Lea Seydoux even sports a Naomi Watts bob), Louis is a psychopathic incel who stalks Gabrielle after an encounter in a nightclub. In each time period, either Gabrielle or Louis is overwhelmed with anxiety regarding a metaphorical “beast” that will completely obliterate them.

As Bonello has widely remarked, The Beast is a film all in service of its atmosphere of yearning and fear. Cutting at will between the various timelines, each with their own aspect ratio and texture (1910 is shot in 35mm, 2014 in digital, 2044 is digital with academy ratio), the aesthetic and tonal instability of the film inhabits a sense of being trapped in the self, ping-ponging between different fantasies, fearful of the future, scared to confront the past, in utter panic about the present. As the time periods emerge as palimpsestic layers, it’s a self-consciousness that emerges as the aforementioned beast. The dread of 1910 and 2014 surely hang over Gabrielle, but it’s not just the narrative fatalism that The Beast mourns, it’s a trajectory of human expressionism, slowly whittled away by the ruthless dehumanization of socioeconomic optimizations. The weight of the film is that of history, and the inescapable knowledge of that history (this central atmosphere of societally and self-inhibited desire also makes this a potent queer film). “The catastrophe is behind us. We’re bored shitless.” says a group of girls in 2044. It’s too late. Humanity and love have died, and the beast lies not within a specific event, but in the aching realization of emptiness, and the sense that within the sweep of time, humanity has been leading to this moment all along (One of thinks of Adele Haenel in Nocturama: “It was bound to happen”).

Bonello has created his most ambitious, most tortured film yet. The Beast refuses to ground itself in any specific time period, treating them as associative nightmares. The film opens in 1910, introducing the 2044 section in voice-over to an extended zoom into Seydoux’s face, the purification of humanity predetermined in Seydoux’s subconscious. Later in 2014, Seydoux spontaneously cries to a lip sync performance of Roy Orbison’s Evergreen, a song which features in the film’s final moments. Her human response to an unknown future is so powerful that it seemingly causes an earthquake. Similarly, the elemental demise that befalls Gabrielle and Louis in 1910 nearly supernatural, the pair drowning in the fires of technology after Gabrielle rejects Louis. Even in 2044, Gabrielle’s memory of her past is incredibly selective. She remembers Louis, but other rhymes remain unaddressed. One of the film’s most inspired choices is the use of Schoenberg’s Verlarkte Nacht, a post-Romantic piece as the composer found his way to atonal music. Initially played over an interlude of archival imagery from the Paris flood, Bonello uses the piece, which heralds nothing less than the death of romanticism at the hands of modernism, as the sound of history. The piece reappears at the very end of the film, and Bonello’s ironic transition (and implied continuity) from Schoenberg into the warm sonority of Gina Paoli’s Sara Cosi and the eternal love of Roy Orbison’s Evergreen constitutes the most devastating use of music in years. Discussing Schoenberg in 1910, Louis argues that music which withholds sentiment aspires for the primitive, granting a human experience we haven’t felt in a very long time. With his overtly reflexive use of genre, texture and surface, that’s exactly what Bonello has achieved.

One of my favorite things about Bonello is his conceptual audacity. He’s a director willing to try anything, and the sheer ingenuity of his visual metaphors is primal. Seemingly throwing out one crazy idea after another in an attempt to simulate all the noise that prevents us from being present, The Beast has an unhinged agitation. Dolls have been a mainstay in Bonello’s work since the beginning of his career, a symbol of our powerlessness in the face of larger systems of power (think Cindy: The Doll is Mine, Adele Haenel’s porcelain routine in House of Pleasures, the mannequins and models in Saint Laurent, Nocturama, and Zombi Child, the Superstar scenes in Coma). Here, as humans become increasingly robotic, dolls become increasingly human (Gabrielle’s husband owns a porcelain doll factory in 1910, a cigarette smoking, sunglass wearing plastic doll named Cindy is one of Gabrielle’s only companions in LA, and in 2044, a doll is played by Guslagie Malanda of Saint Omer fame), their trajectory a beguiling mirror to humanity’s. Fortune tellers recurse through time, appearing most creepily in 2014, within a mass of popups including pornography ads and Trash Humpers footage. Somehow, pigeons, minions of fate and possible AI robots, become a symbol of disaster to come. Bonello, contemporary cinema’s great practitioner of pop music, shows us humanity through the evolution of dance. By the time we get to 2044, there’s a series of clubs, pared down to a futuristic space themed after a different year every night, as the future is obsessed with specificity and completely devoid of contemporary expression. An ironically labeled “free zone”, the mannered dancing of purified souls turns pop catharsis into a reminder of the empty contemporary (all enhanced by intertextual connections to this scene of Lea Seydoux dancing in Saint Laurent). These visual ideas are so destabilizing, so haunting and disruptive, that they achieve a cumulative transcendence.

The Beast is perfectly encapsulated by its opening scene. Lea Seydoux, either in a fourth-wall-breaking scene or in the 2014, is practicing a shriek of terror in front of a green screen that engulfs the frame (a scene that resonates with everything from the end of Twin Peaks: The Return to the opening of Blow Out). The metaphor of the beast is everything and nothing, it’s the ambiguous authenticity of the acting and the scene as cinematic reference, it’s the digital mediation of the pixels that make up the screen and the anxiety of the act of being recorded. Bonello doesn’t offer solutions in The Beast, but the humanity underlying his anxious simulacrum of the present provides cathartic hope.