Sink or Swim

In which I try to describe a revelatory viewing of Su Friedrich's Sink or Swim

I’m admittedly not the most knowledgeable about experimental film, but I’ve been meaning to watch Su Friedrich’s avant-garde autobiographical film Sink or Swim for months now. Recently, I found it on Kanopy (becoming one of my go to sources of late). I thought it would be fun to write about a movie which I’ve heard a lot about but don’t have much of a firm context for.

Sink Or Swim is composed of 26 vignettes, with a title card containing a single word preceding each section. These title cards are ordered backward alphabetically. The first is Zygote, the second is Y-Chromosome, the third is X-Chromosome and so on all the way to Athena/Atalanta/Aphrodite. Each section is voice-over narrated by a young girl in the third person who shares everything ranging from memories of childhood told from both her perspective and her father’s, to Ancient Greek myths, to her hopes, dreams, and nightmares. While these voice-overs only occasionally have a direct relationship to the visuals, a few themes are readily apparent: a strained relationship with abusive parents, connections to mythology, and a water motif.

Very broadly, the voice-over narration is chronological, but is constantly scrambling time in its disembodied narrator, who is speaking from the future, but is audibly too young to be discussing the events in question. Many of the ideas of the film are present in the very first segment: Zygote. Sink or Swim opens on a mass of sperm presumably on their way to fertilize an egg, tails waving madly under the microscope. As an egg does eventually get fertilized, the girl’s voice is born, reciting the myth of Athena’s birth starting with explanation of Zeus’ failed marriage with Hera, to Athena jumping out of her father’s head fully formed, deemed a goddess of war, given the responsibility of wielding Zeus’ terror-inducing shield. The relationship between the girl and Athena seems fairly self-explanatory: a newborn, undeveloped being, with knowledge beyond her years, literally a growth of the father’s consciousness, powerful yet embodying the horrors of war is an apt corollary to the appearance of this narrator, who herself is still an unformed child, as zygote, before life even begins, narrating the mythological past, carrying traumas of the future.

The title of the film comes from an early section: Realism. When the girl asks her parents to teach her how to swim, her father throws her into the deep end of the pool telling her to find her way back. The narration is ambiguous in its retelling of this story: “She panicked and thrashed around for a while, but finally managed to keep her head above water. From that day on, she was a devoted swimmer”, able to be taken either as a daughter learning to love swimming, or as a daughter becoming a devoted swimmer out of necessity, lest she drown at the hands of her father. This ambivalence towards water takes further shape as Realism ends with the girl remembering a joyous summer at a New Hampshire Lake where her father taught her about water moccassins, which exist at the bottom of bodies of water, ready to cover humans with poisonous bites. Even after the girl checks an encyclopedia entry and discovers that water moccassins don’t live anywhere near New Hampshire, “a geography lesson wasn’t enough to comfort a girl”.

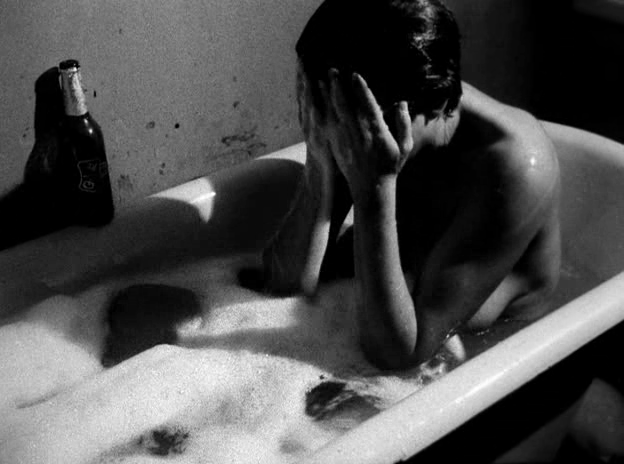

From this point forward, water becomes a mythical space of love and death. A particularly disturbing example which has clear parallels to the swimming story is that of Loss, in which the father punishes his daughters by taking to the bathtub, turning on the faucet, and shoving their faces in the water, choking them for disobeying their mother. Onscreen, we see two girls, presumably the sisters, walking amiably through what looks like a wedding scene which abruptly cuts to black once the voice over begins to describe the father’s punishment. In the section Kinship which comes directly after, the shower becomes a mythical space of ambivalence, containing death and familial trauma, but also the roiling intensity the young girl’s homosexual awakening. The sequence features two women. One is in the shower while the other is getting up from a nearby sauna. Interspersed between sequences of woman 1 in the shower and woman 2 in the sauna are travelogue-style videos of what looks to me like the desolate desert of the American Southwest, whose trying climate is relieved by a small oasis and a splash of water on a windshield. The first overtly sexual encounter between the two women is preceded by an extended shot of the ocean as two birds struggle against powerful currents. A quick cut to black. A still of the woman in the shower gasping for air (or in relief?). The other woman entering the frame to meet the open mouth with an embrace that reads as sexual but also overtly therapeutic: a necessary comforting embrace. Water as a conduit for salvation and condemnation, suffering and pleasure. There’s perhaps even a bit of reference to Hitchcock’s Psycho here. Shower sequence that portends death through two past references one filmic, one personal, but becomes a passionate love sequence, one which has the intense, almost taboo, ecstasy of forbidden homosexual desire being fulfilled, but also strikes me as akin to an understanding embrace from the future to the past.

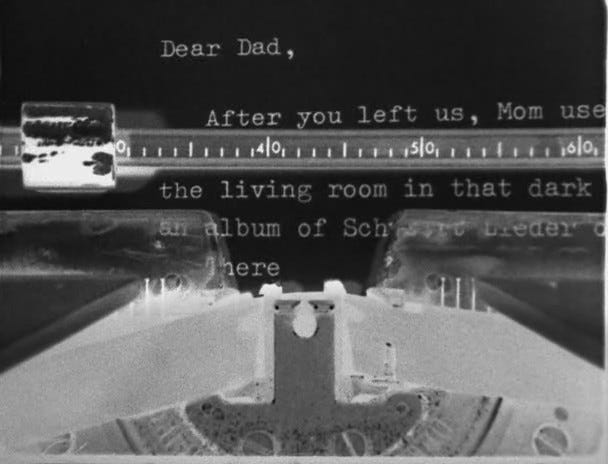

The young girl’s narration is absent in Kinship. Instead, a Schubert Lieder soars over the footage. This Schubert lieder comes up again in the section titled Ghosts. This story also lacks voice-over but contains negative footage of a letter being typed via typewriter. The letter tells of a song that the girl’s mother used to play after their father left.

“Dear Dad,

After you left us, Mom used to come home from work, make us dinner, send us to our rooms and then sit in the living room in that dark orange armchair and play an album of Schubert Lieder over and over again.

There was one song I particularly loved. I never knew what the lyrics meant but it was the one that made Mom cry the most. We would come in and tell her we loved her and we promised to be good so that you would come back again.

I recently got a translation of that song, "Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel". Do you know it already? It's the one about the woman who yearns for her absent lover and feels she cannot live without him.

It's so strange to have such an ecstatic melody accompany those tragic lyrics. But maybe that's what makes it so powerful: It captures perfectly the conflict between memory and the present.

Love,”

Then the punchline:

“P.S. I wish that I could mail you this letter.”

I’m not even going to try going into detail about the ways Ghosts makes Kinship retroactively even more powerful, but I will say that a lot of Friedrich’s vignettes work in this mysterious way, where they recontextualize the segments before and after in indescribable ways, creating webs of emotion between audio and video past present and future, and audio and audio past, present, future, oftentimes even including emotional whiplashes within just a single segment that creates significant reverberations. Take the segment titled Memory, which begins with silent, flashing, footage of 3 children playing on a field. There’s an assumption that this could be a positive memory of childhood from the girl’s point of view, but instead after watching these children playing for 25 seconds, the girl’s voice over informs us that this is actually a memory of the father, whose sister died from a heart attack after jumping into a lake. The clips onscreen begin to fade in and out as the girl describes her father’s personal guilt over the death of his sister. Then, within the same segment, Friedrich jumps ahead 20 years to the girl and her father, just at the time of the girl’s birth, where her father wrote a letter imagining the girl all grown up, but also an extension of his dead sister. The passage is so beautiful that I’ll paste it here.

“He realizes that no one can predict the course of a child's life, but tries to imagine her as a young girl running off to school or as a grown woman with a life of her own. He ends the meditation by saying, "All this must come as the questions are answered, but now there is only the quiet face that replaces a drowned sister at last."

Friedrich, by putting these vignettes in the same segments, within the same breath, creates implies causality between the grief of the sister and the birth of the daughter and graces said causality with mythical weight through its reference to the birth of Athena, an extension of the horrors within her father’s head, fully grown at birth with knowledge of the past and future.

Friedrich’s film is a bracing experience because of its restraint. It’s confident in the simple rigidity of its construction and observation to create moving emotional atmosphere. Its contrast between intimate home video vs rigid structure vs objective voice over narration suggests an overwhelming desire to process, but as any audience member can feel, there’s no way to fully process life’s trials and tribulations.