NYFF: Dooni, towards a fundamental theory of physics, Morning Circle

Dooni (Kevin Jerome Everson, Claudrena N. Harold):

The latest miniature of Black life from Kevin Jerome Everson and Claudrena N. Harold looks to the history of disco. Set to Timothy Johnston’s recitation of preacher Walter Hawkins’ eulogy for queer disco icon Sylvester, Dooni’s imagery consists of swirling, dancing, black bodies bathed in the neon glow of mirror plated disco balls.

The images are uniformly beautiful, at times reduced to impressionistic brushstrokes of blacks, blues, and pinks with occasional discernible expressions of ecstasy. Divorced from the rush of Sylvester’s music, there’s a melancholy that’s further emphasized by awareness of Trump 2.0’s progressive persecution of trans communities and the disproportionate rates of violence towards black, trans women.

Sylvester, who died from AIDS complications in 1988, passed during another fraught period for gay acceptance in the United States. Hawkins’ eulogy, which is filled with religious reference, urges the audience to resist staying silent. Consistently re-iterating that “AIDS is not god’s punishment”, Hawkins eventually bursts into song so the joyous figures dance through the elegiac sermon, as if dancing to Sylvester’s spirit. Using a historical event to raise a mirror to our current political moment, Dooni is a memorial and contextualization, an invigorating reminder of hardship overcome.

towards a fundamental theory of physics (Victor Van Rossem):

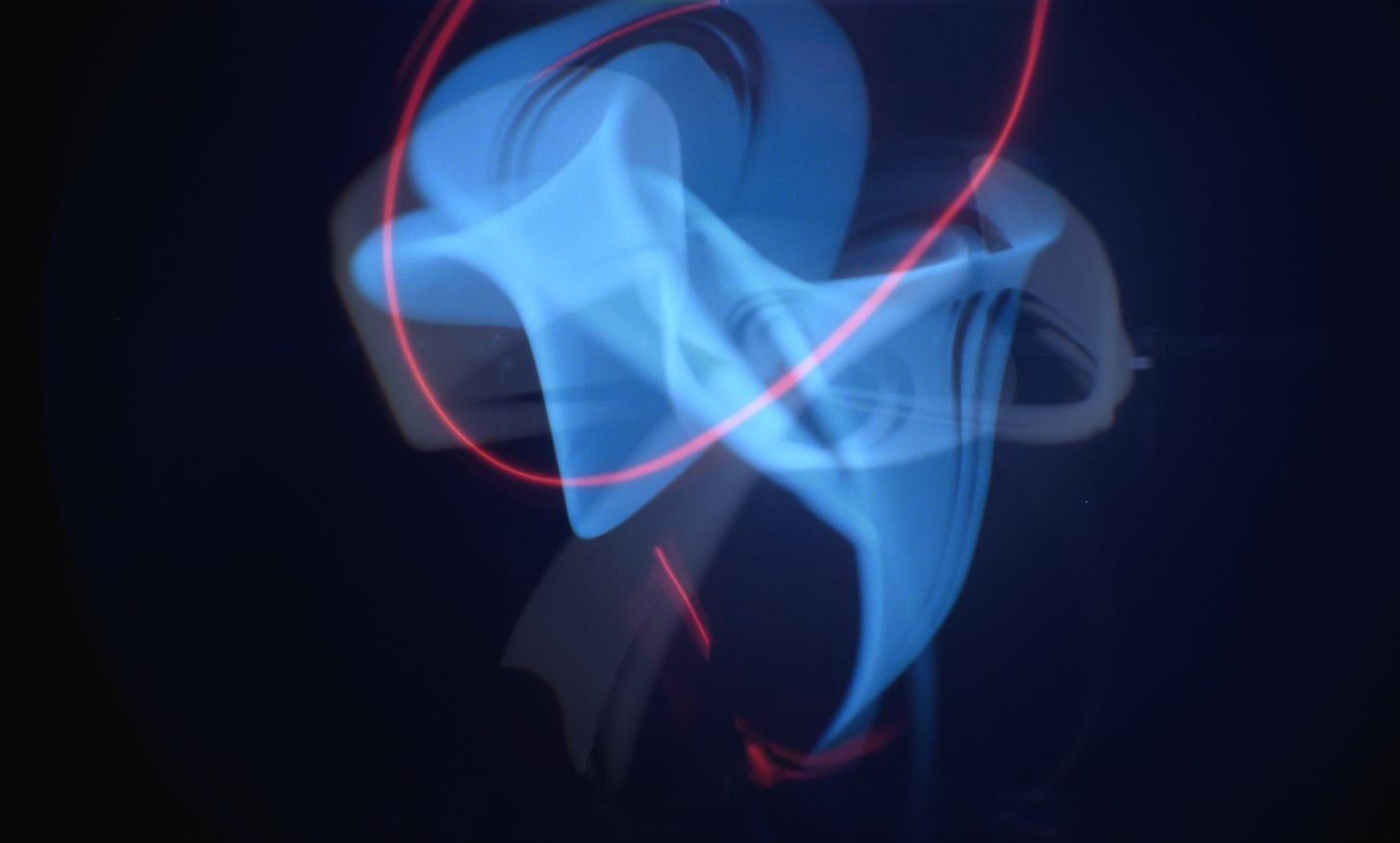

Victor Van Rossem’s 3D short towards a fundamental theory of physics was made with a modern recreation of Tim McMillan’s time-slice camera. Using 293 cameras arranged in a circle, each loaded with 16mm film, Van Rossem isolates and gracefully revolves around moments frozen in time, and the otherworldly ribbons of light that form the basis of cinema.

This is a film that strips cinema to its foundations, examining the ineffable mysteries of physics. At times, quirks in the time-slice will result in jittery motions, or pieces of abstract light formations flaring out in strange projections. Whatever screensaver associations we have with Van Rossem’s imagery are offset by the tactility of 16mm film and the conceptual disjunction of time and space. towards a fundamental theory of physics is a film that qualifies as “pure cinema”, and a worthy experimental film for its ability to show new ways of understanding the moving image.

Morning Circle (Basma Alsharif):

While many Palestinian artists are understandably focusing their attention directly on the ongoing genocide, the latest film from one of the country’s greatest experimental filmmakers, Basma Alsharif (We Began by Measuring Distance, Home Movies Gaza), is about the experience of exile. Opening in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz, a Badalamentian score accompanies a crane shot as it snakes its way through the streets and creeps into a nondescript building. Eventually, Alsharif’s camera settles on the silhouette of a man, Adnan, framed between windows made to look like cell bars, as he is questioned by an immigration officer whose interrogation implies that Adnan and his family are unwelcome (“Can you go back? Do you have family here?”).

In Morning Circle’s first revelation, the space is revealed as the Adnan’s home, where he, a single father, wakes up his son to get ready for kindergarten. In this moment, Morning Circle’s general premise becomes clear, delineating the encroachment of public policies towards migrants onto their private spheres, implicating the audience’s gaze as a conduit of the state. The film hinges on the disconnect between the hostility of the questioning and the care Adnan shows his son, evident in the gentle way he clips his son’s nails and puts on his mittens.

The film’s dissonances are exacerbated once the son gets to school, and Alsharif subtly shifts the film towards his subjectivity. Scared of leaving his father and being dropped off, the son is invited by a pair of kind teachers to join morning circle. Interspersed with black frames paired with the immigration officers questioning, this act of community building is subverted and eventually portrayed as an assaultive incongruence. To the blaring sounds of Maurice Louca’s Benhayyi Al-Baghbaghan (Salute the Parrot), the illusory safety of a school setting becomes a maelstrom of the child’s confusion, featuring superimpositions of footage of Palestinians returning to Israel’s wreckage of North Gaza, tracking shots of communal spaces, and negative images, spinning in opposing directions and occasionally in reverse, of other children dancing with their teachers. The whirlwind of competing sentiments inevitably affects the son, and in a heartbreaking punctuation mark, the film ends with him stumbling on the sidewalk.