Notes on Films by Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler (1964-2023) - 3/5

Program 3:

The centerpiece of this program is Hours for Jerome, Dorsky’s 50 minute film edited from footage shot in the Stone House and San Francisco. This program feels intrinsically tied to the previous, as both concern this formative time when both Dorsky and Hiler were working towards successfully creating polyvalent montage and not distributing work. Hours for Jerome is bookended by two Hiler films, Bagatelle I and Bagatelle II, the second of which also utilizes this personal archival footage.

The preceding short was Christopher Harris’ 28.IV.81 (Bedouin Spark). I found it quite evocative. In a black and white close up of a glitter bottle, we see stars floating in viscous liquid. As the light plays off of these stars, feelings of wonder, loneliness, and nostalgia are evoked. The connection to Dorsky/Hiler is clear, and 28.IV.81 actually accentuates the frustration in much of Dorsky and Hiler’s footage. Dorsky suffered from an artistic block through much of this period and in one of the interviews in the Canyon Cinema book, Hiler discusses the isolation and estrangement he felt in these unfamiliar landscapes.

Bagatelle I (Jerome Hiler, 2018), Bagatelle II (Jerome Hiler, 2016):

I confess to not jotting down a ton of notes after these two, but I loved both.

An extension of an idea from In the Stone House animates the opening of Bagatelle I. Instead of using icicles as a method to scratch on film, Hiler wildly moves around a tree, the shape of the branches visually matched with short bursts of hand-scratched film strip. Found this overall less memorable than Bagatelle II, but still loved it.

Bagatelle II opens with black and white footage of a train. Hiler has an interest in the industrial, and another industrial structure forms the film’s final shot. Covers a huge span of time, and that sense of condensed memory is powerful. The brevity is key. The core memory of these films, but especially Bagatelle II is motion, the dance-like quality of the works, and the sheer luminosity of the imagery.

Hours for Jerome (Nathaniel Dorsky, 1982):

Was initially surprised by this film’s relative mundanity. Much of it plays like lyrical, impossibly well-made home video. Dorsky experimenting with polyvalent montage (his first “successful” attempt would be Triste, released over a decade later), but the film has recognizable sequences, and with its recurring cast of characters, is the closest to a narrative film that I saw all weekend. Take a sequence early on that recounts trips Dorsky and Hiler took into the city, cutting from silhouettes in front of a large aquarium to a static shot of two rhinoceros.

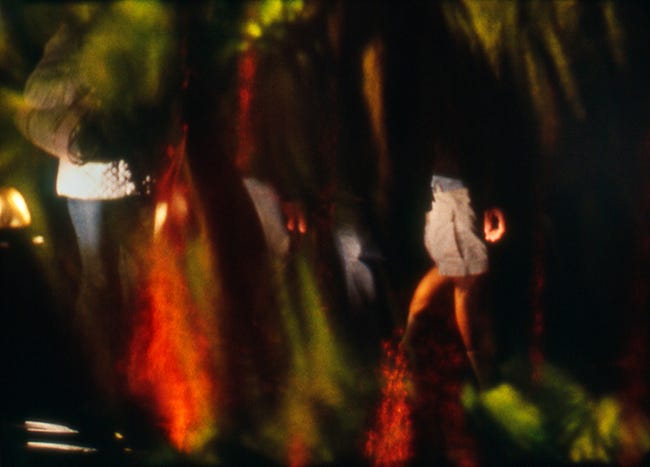

The film moves between city and country, and the general trajectory once again follows the seasons. Shots recur in the various times of year, which also means we see rhymes between the film’s two sections, the first spanning winter and spring, the second spans summer and fall. Long shots of landscapes have a more pronounced presence compared to some of the other Dorskys, and the film includes multiple time lapses, both over verdant fields and snowscapes. Lots of clouds as well. Two shots of people walking in that 18fps. Many shots of cars, one funny one includes a bright red car cruising on the highway. Shot of cars driving under a bridge (pictured at the top of the post), is one of my favorite shots ever. Light has never looked so silky and diaphanous. Dorsky’s moves towards polyvalence also grant the film a wide range of formal experimentation. Mundane shots of Jerome and Dorsky can be placed next to shots of trees where the camera is wildly zooming in and out.

People play such an important role. It’s a beautiful film visually of course, but also beautiful as a remembrance of time spent in the Stone House. Interesting to see the corollary footage from some of the shots from In The Stone House. For example, we see the lake footage Dorsky was shooting in one of the shots from Stone House. Snakes recur between the two films, as does the interest in celestial bodies. One of the most whimsical shots of the film is of the moon, which Dorsky uses as a cutout in the frame, creating 4 circular holes in the frame across the bottom left to top right diagonal. Other shots will have resonance in Hiler’s New Shores. A Halloween party with scary masks plays a role in that Hiler film. Ends with a trip to New York City.

The difference between this film and Hiler’s In the Stone House is clear. Dorsky’s is more leisurely paced, and his formal experimentation often feels more tender. Hiler’s films, which contain so much movement, are inherently first person, but that intimacy is a lot less tender than say, a shot where Dorsky zooms in and out of the fur of his and Hiler’s cat. Hiler’s films often feel like they’re also guided by some supernatural musical superstructure, Dorsky’s have a greater sense of possibility. Brilliant in different ways.