The Phoenician Scheme (Wes Anderson, 2025):

As an aristocrat adventuring across the fictional country of Phoenicia looking to fund an extravagant infrastructural production, the protagonist of The Phoenician Scheme, Zsa Zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro), sees Wes Anderson finding himself in a character whose obsession with the bottom-line compromises his fundamental humanity. Korda, who is emotionally detached from his 10 children, beleaguered by visions of heavenly judgment, and under constant threat of assassination, is a man whose ruthless business dealings have left him in a state between life and death. Due to a recognition that continuing down this path will result in his heavenly demise, Korda reconnects with his estranged nun-in-training daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), conditionally promising his fortune in exchange for her company on the grand scheme for funding.

With its linearized narrative and singular focus on a troubled father-daughter relationship, The Phoenician Scheme blends the intimate character dynamics of Anderson’s early films and the formal extremity of his late style. The tension between the two modes of Anderson’s filmmaking makes The Phoenician Scheme a memorably strange project. In some cases, the episodic narrative relies on characters in a manner incongruent with Anderson’s increasingly spectacular sensibility. This means that the quality of The Phoenician Scheme’s distractingly cameo-defined segments varies wildly depending on the strength of its guest performers (Jeffrey Wright’s and Benedict Cumberbatch’s are great, while Scarlett Johansson’s and Riz Ahmed’s feel throwaway). Given the inconsistency, there’s something overly-telegraphed about The Phoenician Scheme’s narrative progression, which clearly moves from more exotic farces to familial negotiations.

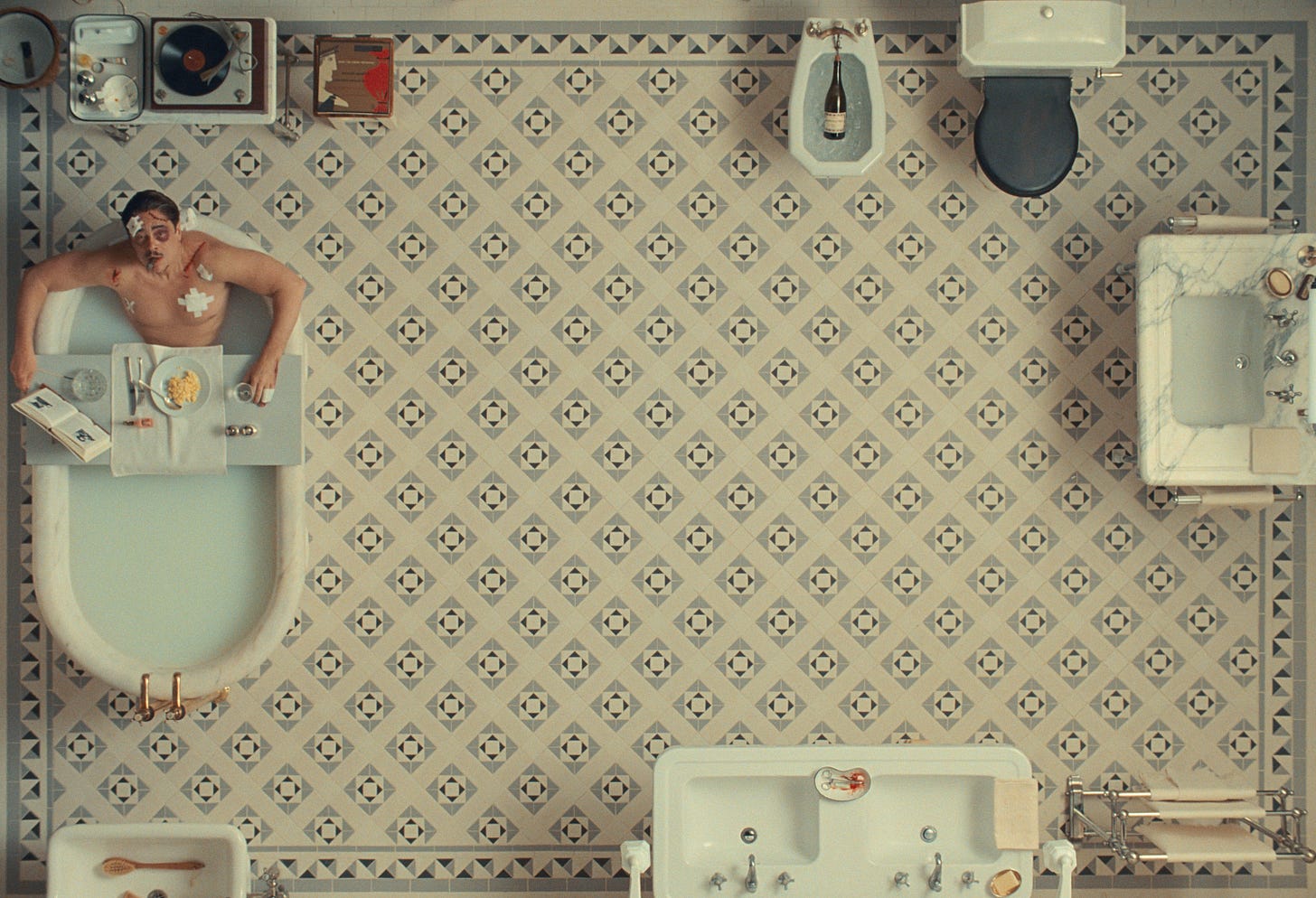

On the other hand, there’s an effective urgency to the combination of Anderson’s dioramic frames and The Phoenician Scheme’s autobiographical bent. The dollhouse quality of Anderson’s style is foregrounded in the opening, which includes a sequence filmed entirely in a static overhead shot. While Anderson’s recent work can feel like they position the auteur as a divine puppetmaster, sequences such as this one, which include an Andersonian figure as their subject, in conjunction with The Phoenician Scheme’s invocation with higher powers, create an uneasy feeling of surveillance.

The Phoenician Scheme is most effective when it takes advantage of the relationship between Anderson’s meticulous frames and the weight of a guilty conscience. The most powerful moment in the film releases this underlying tension. It takes place during a climactic encounter between Zsa Zsa and Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch), a man who may have killed Liesl’s mother and like Zsa Zsa, is presumably responsible for global strife. The release of familial resentment is communicated through a terrifying close up of Cumberbatch’s contorted, bearded face. Nubar’s disfiguration and the shot’s stylistic deviation memorably unleash The Phoenician Scheme’s latent horrors. It’s one of the most striking shots in Anderson’s body of work. While The Phoenician Scheme grants both Zsa Zsa and Nubar (arguably undeserved) redemption, the visceral extremes of Anderson’s form and the film’s occupation with cosmic reckoning form a discomfiting cautionary tale for the uber-rich. The world is watching, and the time to make amends is running out.

The Phoenician Scheme is distributed by Focus Features and is in theaters now.

Vulcanizadora (Joel Potrykus, 2024):

Vulcanizadora is the devastating post-script to Joel Potrykus’ cinema of mid-western relaxers. Potrykus stars alongside his frequent collaborator, Joshua Burge, as Derek and Marty, a pair of old friends embarking on a hike to execute a secretive mission. Although Potrykus tactically withholds the purpose of Derek and Marty’s excursion, providing only glancing references to failed marriages and felony charges, it’s clear from the first profile tracking shot that the pair’s jovial conversation has a despondent streak.

Derek and Marty reveal themselves as two men in conflict with the passage of time. They both harbor an aura of arrested development, and some of Vulcanizadora’s most painful sequences observe the pair’s attempts to recreate the past in a dramatically different context. In the false escape of the woods, they produce Jackass-style videos on cassette tape camcorders, unearth magazine pornography, and dance in zany neon masks. The anachronistic textures of Derek and Marty’s young adulthood, which expand beyond stretches of early digital to include bursts of blown out black and white film grain, are placed within a largely funereal work of long takes and elegiac dissolves. Despite their attempts to relive their glory days, Derek and Marty are bounded by the cold reality of the present.

It bears mentioning that Vulcanizadora is incredibly cinephilic. The first hour qualifies as a spiritual remake of Gerry, the music, which fluctuates between metal and opera, is a descendant of Van Sant’s usage of Elliott Smith in Paranoid Park, and the hopeless rendering of suburbia refers to both Kelly Reichardt and Harmony Korine. The invocation of these films connects Potrykus’ project to his characters. Van Sant, Reichardt, and Korine were American filmmakers who were able to sustain careers regularly directing uncompromising, formally challenging productions. That these films, which include a Béla Tarr pastiche starring Matt Damon and Casey Affleck and the utterly idiosyncratic Gummo, were released by major studios or garnered cult status feels inconceivable now. Vulcanizadora is an estranged sibling from this era of independent cinema, faithful to both the ethos of the period and its director’s distinct personal vision of basement-dwelling slackers. In addition to being a heartbreaking tragicomedy of obsolescence, Vulcanizadora grieves a bygone cinematic landscape.

Vulcanizadora is distributed by Oscilloscope Pictures and available on VOD.

Materialists (Celine Song, 2025):

After Celine Song and husband Kuritzkes released a one-two punch of love-triangle films in Past Lives and Challengers, Song’s follow-up, Materialists, continues the trend, this time following a 35 year-old matchmaker, Lucy (played brilliantly by Dakota Johnson), who must decide between Harry, a rich man who’s perfect on paper (Pedro Pascal) and John, the broke ex whom she actually loves (Chris Evans). While Materialists is ultimately a mixed-bag, it does represent an improvement upon Song’s anodyne debut. Song has clearly improved as a visual stylist, ditching some of the decorative, distractingly metaphorical images from Past Lives to revel in the steely gloss of Manhattan, and for a decent stretch of the film, demonstrates a clever self-awareness, leverages the most frustrating tendencies Song demonstrated in Past Lives towards a larger goal. The hollow schematism of Lucy’s potential love interests, the ensemble’s alien affect (Dakota Johnson’s Lucy in particular seems to only talk in platitudes), and the constant reference to the film’s themes (“it’s just math!”, “you check all the boxes!”) are all coherent under Materialist’s satire of transactional relations.

The opening section, which follows Lucy as she explores a superficial relationship with Harry, functions well as a bitter post-modern comedy, but Materialists can’t decide whether it wants to satirize its characters or romanticize them. A tonal shift is clumsily orchestrated by a mid-film development concerning one of Lucy’s clients, Sophie L, who is assaulted on one of her dates. The revelation that a man who is suitable in the abstract might be a terrible person shakes Lucy to her core, causing her to re-evaluate her belief in love.

There are a slew of narrative contrivances that make this unconvincing, but what hinders Materialists is its ensuing investment in character relations that were posed as strictly theoretical. None of the more conventional scenes between Johnson, Pascal, and Evans, who were all seemingly cast for their mannered screen personas, work. Song’s script, which includes lengthy monologues where the characters muse on the relation between love and capital, are unsuited for conventional romance and largely restate the same message: that love isn’t just a mathematical equation. Materialists has thorny edges that are specific to these characters and the film’s contemporary setting (e.g. how the political and economic conditions of 2025 produce the bigoted, predatory “non-negotiables” of Lucy’s clients), but it circles the drain on its blandest insights. It’s maddeningly inconsequential.

Materialists is distributed by A24 and is in theaters now.